For those who study critical theory in the humanities, the names are familiar: Derrida. Lévi-Strauss. Cixous. Foucault. Said.

This particular list goes on: Spivak. Butler. Nancy. Agamben.

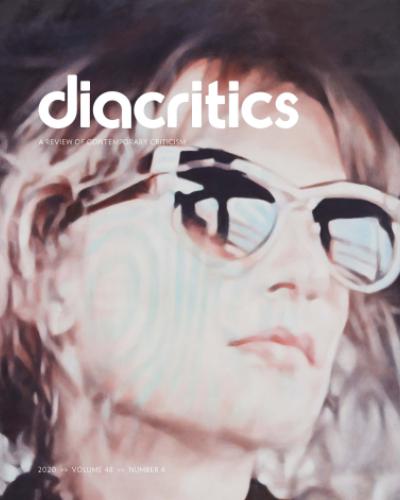

An astonishing number of foundational critical theorists has appeared in diacritics:A Review of Contemporary Criticism, which turns fifty this year. Conceived in 1971 as a forum for thinking about contradictions without resolutions, the journal marks its half-century anniversary in a world seemingly far-flung from its origins. Now is a time of the internet and blogospheres, of recognizing the grip of climate change and weathering a global pandemic. Yet, conceptually, diacritics is still, as it always has been, very much at home.

In the five decades since diacritics was born in a downtown Ithaca office, its cutting-edge and even at times quirky approach to critical theory hasn’t changed. The journal still brings the work of young up-and-coming scholars into a shared space alongside major theorists. According to its website, its goal is to offer “a forum for thinking about contradictions without resolutions; for following threads of contemporary criticism without embracing any particular school of thought.”

That forum is available in both hard copy and online: remarkably, in a nod to the journal's ability to adapt to the 21st century, all of diacritics has been digitized: a complete archive of the journals’ past issues and the conversations within is available on the journal’s website, via Project Muse.

Now, under the guidance of editor Karen Pinkus and managing editor Hannah Miller, the journal is celebrating a half-century of publishing rigorous, deeply original, sometimes eclectic scholarship that embraces a plurality of theoretical approaches and critical perspectives.

Reaching back into the past

To acknowledge this milestone during a pandemic year, members of the diacritics board decided on an approach that virtually bridges not only spatial but also historical and conceptual distances: an anniversary blog series. They sent an open call for submissions to the diacritics blog to former contributors, authors, and editors alike.

“The idea was to get people who have contributed to diacritics in the past to talk about their experience with the journal, and how they got involved with it, and how their thinking on their writings has evolved over time,” Miller said. “We wanted to ask people to reflect on how things have changed and what the journal meant to them.”

In doing so, Pinkus, Miller and the diacritics board wanted to encourage the sharing of ideas, while giving contributors the freedom to express themselves in a format of their choosing. The open nature of the anniversary blog series would also allow authors a degree of flexibility, as the board was conscious of how colleagues may have been feeling overworked and burnt-out after the events of the past two years.

The first four contributions to the series are already available on the blog. All have created a space for thoughtful, informal but deeply intelligent reflection on what diacritics has contributed not just to the field at large, but to individual careers.

In the first series entry, Georges Van den Abbeele, now a Professor of Humanities at the University of California, Irvine, recalls how the journal was what initially drew him to apply for his PhD in at Cornell.

“I was just blown away by the whole thing,” he writes. “The style of the articles, the interviews, the elevation of the humble book review into a theoretical juggernaut, and of course, the supporting and often outrageous art design (such as the infamous ‘peanut butter and no jelly’ issue, or the mesmerizing cover illustration of ‘the letter D-constructed,’ among many, many others).”

The art design has held a prominent place throughout diacritics’ history.

“The journal had a unique look from its very beginning, compared with other ‘theory’ journals,” Pinkus said, noting that there have been several long-standing art editors over the course of the journal’s history. Diacritics also now features an artist in each issue, with art appearing not just on the cover, also between essays.

“The art is not meant to "illustrate" the essays (unless, of course, we are talking about a few issues or essays where the art is precisely "illustration"),” Pinkus said, “but rather, it is autonomous and stimulating, creating a kind of conversation with the essays themselves, especially to the degree that contemporary art tends to be engaged with theory.”

This approach contributed to diacritics’ anachronistic appeal.

“diacritics was an academic journal like no other, and that overwhelmingly appealed to the anarchistic sensibility of my youth and continues to appeal to my critically cantankerous older self," Van den Abbeele said.

Where Van den Abbeele’s blog contribution nods toward how the journal can play a profound role in impacting scholarly careers, Zoë Sofoulis, an Adjunct Research Fellow and member of the Institute for Culture and Society at Western Sydney University, points to the impact diacritics had in providing her with a platform to declare a new intellectual project.

In an interview with Pinkus, Sofoulis discusses the impact of her 1984 article, “Exterminating Fetuses: Abortion, Disarmament, and the Sexo-Semiotics of Extraterrestrialism,” her first published academic article.

“Reading it now I am struck by how bold I was, especially proclaiming the project of a sexo-semiotics of extraterrestrialism,” Sofoulis says. “It’s the kind of thing blokes do, but I was too naïve in the ways of academia to understand that it is extremely rare for a woman to be recognized as a systematizer or an inaugurator of some minor sub-branch of some area of study, or even for the name of her project to be taken seriously!”

Stories like these are a testament to what Pinkus calls diacritics’ “eccentric, even punk aesthetic,” a description that hews closely to the journal’s definition of eclecticism in the humanities: “nurturing work that is transhistorical, creative, and rigorous.”

The novelist, poet and literary critic Alicia Borinsky, whom Matías Borg interviewed for the anniversary series, perhaps describes best diacritics’ impact, both past and potential: “diacritics has my vote of confidence; it’s always been a great polemical journal and very much alive.”

A ‘turn’ toward the future

And diacritics is always looking ahead. According to Miller, the journal’s trajectory has always followed that of the discipline, reflecting new intellectual trends within the field of critical studies.

The journal’s most recent blog contributions have included a commentary on Nancy’s scholarship by Irving Goh (’12, National University of Singapore); and an interview with Professor Emeritus Neil Hertz (Cornell, Johns Hopkins) on his special Spring 1983 diacritics issue about Freud and Dora.

The journal has additional plans to publish two more anniversary blog contributions through Spring 2022, including a new Jean-Luc Nancy translation and an interview with Emoretta Yang, the journal’s former graphics editor.

Upcoming issues will include “The Turn II” – the second of a two-part special issue (with guest editors Andrea Bachner and Carlos Rojas) on the phenomenon of the turn, which focuses on how intellectual and methodological turning points result simultaneously from both revolutionary paradigm shifts and more subtle and modest shifts in direction.

Other planned special issues include “Rethinking Black Resistance (with guest editor Linette Park); issues on Women and Theory (with guest editors Tracy McNulty and Erin Graff Zivin) and on Deceleration (guest-edited by Patty Keller and Rhiannon Welch); a special issue comprised of interviews and conversations with scholars about “Heidegger Today” (edited by Pedro Erber and Facundo Vega); and an issue on Walter Benjamin’s text “Fate and Character” (with guest editors Rachel Aumiller, Sam Dolbear, Paul Fleming, Tom Vandeputte).

Here’s to the next fifty years.